Signing the Treaty of Rome - 1957

Part I of an essay of the history and future of Europe from our present day perspective

Looking back: a century of pain and progress

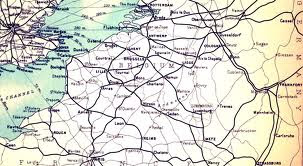

In the decade before the First World War the European continent experienced great commonality across the national and imperial boarders, stretching from the North Sea well into the heart of Russia. Much of this was the result of manifold investments in the second half of the nineteenth century, most notably in rail transport but also new modes of communication such as the telegraph and the telephone. New markets were opened and the emerging new urban classes shouldered a gradual expansion of the economies of most European countries.

Railroads were the first to unite Europe (1900)

The increasing sense of European commonality was furthermore stimulated in the arts, in the world of science and invention, but also in the world of ideas. The emancipation of the working classes and efforts to improve the conditions of labor and their general living conditions became the first and foremost themes to create genuine internationalism among a broad segment of the European societies.

A rather more anachronistic and at the same time contradictory element were the close connections between the monarchs of the time and the shared culture of their entourage, which expressed itself both in the area of diplomacy and in the general habits of the European ruling elite. But it was contradictory indeed, because out of their very interaction arose the cataclysm that subsequently took many decades if not the entire twentieth century to overcome.

The outcome of the Second World War and the subsequent East-West division of Europe meant a prolonged social, cultural and political divergence among the people of Europe. But even in Western Europe the old sense of commonality did not return. The old mobile elite had vanished from the scene and the project of reconstruction and development was a national effort first of all for each country.

However, it was self-evident, after the Second World War, that the countries of (Western) Europe should strive to reach lasting settlements to safeguard the continent from any renewed armed Armageddon and that preferably they embark on a broader project of unity. From its start the European Community was embedded in the determination of the member states “…to lay the foundations of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe”. Its main – primary – objective was to facilitate the development of their markets. Despite periodic setbacks this project has been hailed by many inside and outside Europe as an unequivocal success. It created a system of shared rules and instruments without precedent, which benefited all member countries in the broadest possible terms. It became a work in permanent progress, with successive new ambitions not limited to merely economic interests but increasingly covering the wide public domain of social, environmental and judicial affairs.

But perhaps the most significant development for - what became - the European Union has been the gradual enlargement of its membership, in particular when after the fall of the Berlin Wall the lost countries of Eastern Europe could finally rejoin the sphere of European commonality which had been held away from them for almost a century. The perspective of an enlarged common market of over 400 million consumers justified considerable effort – and monetary investment - to help these countries adjust and align with the prevailing regime of steep competitive regulations to which the western European countries had grown accustomed in the course of the preceding decades.

In parallel to the political processes new cultural commonalities emerged but they were not distinctly ‘European’ (continental) and rather more western, much of it being introduced out of the English speaking world, America in particular. A new universe of popular culture supported by rapidly proliferating mass media opened up and this in turn – at least to some extent – helped create a sense of shared interests, especially among the younger generations, throughout the western world.

Governments and their constituents: diverging perspectives

All of the above is the correct historic tale, one could say, but it is not necessarily the story of the European people themselves. For it is equally valid to say that the project of Europe has been – and has remained to this day – a project of the national governments - obviously supported by the business communities – and not a grass roots process. European citizenship is a concept only, however much our national passports allow us to freely move across the continent. For most Europeans, the unity of their countries is a bureaucracy, a powerless and distant parliament and a faceless center of regulations and directives which are rather more perceived as a disastrous overkill than as a genuine benefit.

Yet, in the face of today’s financial and economic adversity it is difficult to determine, however we ‘feel’ about the European Union, whether in fact this adversity has part been caused by a European project that has gone too far (for instance, by pushing the euro as a common currency before every participating country was truly ready) or, on the contrary, whether indeed the project has to be completed (it has not gone far enough) at even greater speed in order to safeguard its benefits for the member countries.

We have to remind ourselves of the fact that throughout the decades, no single destination for the European Union has been formulated – with people on many sides along the way arguing for a strong federal union or, alternatively, for a confederate union which leaves the center of political gravity in the national parliaments. Today, we may ask whether history hasn’t in fact overtaken these various arguments. On the one hand, the course towards stronger central influence seems almost irreversible or inevitable. On the other hand, despite greater unity, the member countries, including those who participate in the common currency, still show great divergence in terms of their political and societal priorities and preferences. The conditions set to save the solidity of our economies (and of the euro in particular) have ignited fierce protest in a number of European countries, reflecting a broader sense of estrangement among a significant segment of the population.

But perhaps the real estrangement is not so much with the institution or governance of the European Union (its new constitution being considered by some as “squalid”) but rather more with each other, between the people of the member countries. It seems as though more than half a century has done little if anything to bolster the broader sense of commonality between the citizens of Europe. We may enjoy a holiday in Italy or Spain but how much closer have we come to appreciate each other’s culture, aspirations and dreams of the future? Across Europe, people have retreated to a verbal trench war to keep everything as it is and they have thrown away the idea of Europe as a shining beacon.

Secondly, many European countries are grappling with the situation at hand, in all dimensions: economically, socially and politically. Across the continent we have become more inward looking, less cosmopolitan and less inclined to fulfill our great historic projects.

Trying to grasp the full picture

Then, there are those who argue that Europe’s crisis is even more profound, reaching to the heart of our civilization and its very continuity. They see our present crisis as symptomatic for a series of structural issues about which people have good reason to be concerned. Their anxieties, they contend, even including outright xenophobia, are only too understandable, however much people might be misguided both by the nature of the issues and the realistic solutions.

It is slightly disconcerting that such comments in particular stem from outside analysts, for instance out of America. Few European commentators come to the same inventory of problems, perhaps in part because they verge on treading the boundaries of political correctness and might be seen as too pessimistic.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to ignore these assessments, in particular where they concern the prevailing demographic trends. Examples are Bruce Thornton’s book “Decline and Fall – Europe’s slow motion suicide” (2008) and Mark Steyn’s “Ämerica Alone – The end of the world as we know it” (2006). Both books were published before the world wide financial crisis hit us and when in Europe the general consensus still was highly upbeat. They nonetheless paint a grim picture that today – more than at any time before – rings many bells of truth.

Apart from demographics (and their longer term economic, social and financial consequences), they see most Europeans as being politically too complacent, too much addicted to a high cost welfare system, inapt in dealing with immigration and integration issues and, perhaps most important, rapidly losing steam in terms of spiritual vitality. In particular they express their severe concern over Europe’s religious indifference, a point of view that may perhaps be most debatable but pertinent nevertheless.

For indeed, without shared underlying values that embrace the entire population, including immigrants and their descendants, Europe’s heritage and its historic potential are bound to obliterate. It is a choice to make, however we define religion or any other source of spiritual inspiration in this context.

Formulating new perspectives

These and similar analyses are reflected too throughout this blog. My main objective has thus far been not merely to underscore the nature and extent of our present day challenges. Most certainly it includes, however modestly, the attempt to formulate new perspectives and ideas which may inspire our younger generations in particular when defining their own themes and ambitions for the world as it will gradually be transferred to them. Still, gaining a good understanding of the past (“how did we get here?”) remains a critical point for any young person who wishes to make a contribution to his or her future world.

We live in a transition period. The old world is coming to an end, the new world is already in the making. Our focus should be on the latter, not on the former. We shouldn’t ignore history and its arguments, but more persuasive are the arguments derived from our perception of the world ahead. And this may well require a new concept for a lasting union among the peoples of Europe and stronger efforts to retrieve and safeguard our commonalities across national borders, wherever we live on this diverse and fascinating continent.

Further links on this topic:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4n5VvWX6D-s

Bruce Thornton (Europe’s slow motion suicide)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQELHJx8Vf0&feature=related

Mark Steyn (America Alone)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bAQTvRXZy-4

Neal Ascherson (British journalist)

http://www.freeworldacademy.com/globalleader/agendacont.htm

Europe civilization is committing suicide

http://www.economist.com/node/16539326

Can anything perk up Europe? (Economist 2010)